By signing in or creating an account, you agree with Associated Broadcasting Company's Terms & Conditions and Privacy Policy.

By signing in or creating an account, you agree with Associated Broadcasting Company's Terms & Conditions and Privacy Policy.

On 1 September 1859, two amateur astronomers from England, Richard Christopher Carrington and Richard Hodgson reported on an optical solar flare. Carrington also noted a large magnetic storm that occurred about 40 minutes following the flare. This remains the largest and most severe solar storm in recorded history. Telegraph stations caught fire, including those induced by arcing. Large voltages were registered at the ends of telegraph wires, with interruptions in transatlantic communications. Auroral displays visible across much of the world, which was a terrifying experience for those living in the lower latitudes. Auroras were recorded in Hawaii, Panama and Santiago, as well as Mumbai in India.

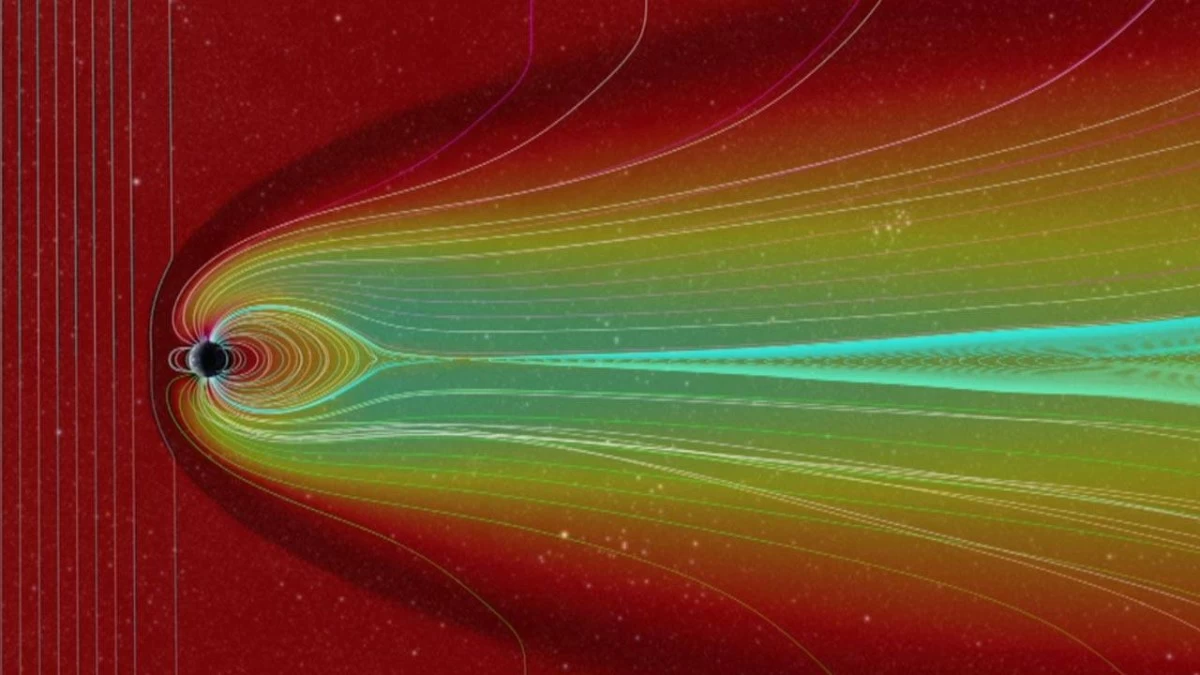

The Sun is essentially a giant ball of plasma, and during these energetic events, a magnetic cloud of charged plasma particles is hurled violently outwards through space, in the form of a coronal mass ejection. Scientists estimate that the coronal mass ejection must have made the trip between the Sun and the Earth over 17 hours. The magnetometers in Europe were driven off-scales. Long-buried geomagnetic observations conducted by the Colaba observatory in what was then Bombay, taken at intervals of 10 minutes indicated a storm three times stronger than any that has been recorded since. The 1859 storm remains among the strongest storms ever observed, with a flare in 2003 being a close contender. In any case, the Carrington Event is the most famous, if not the strongest solar outburst in recorded history.

Solar flares are measured based on the intensity of their X-rays, on a scale that goes through the letters A, B, C, M and X. Anything below a C is considered close to background levels of solar activity. X-class flares are the strongest category of solar flares. The letters are appended by a finer-grained scale that goes from the numbers 0 to 9. There is no upper limit to X-class flares. The solar flare that caused the Carrington Event is estimated to be around an X45. The 2003 X-ray flare saturated the detectors, but is estimated to be between X28 and X45 in intensity. It may just be possible that the 2003 flare was actually stronger than the Carrington flare. There are records of solar superstorms preserved in ice cores and tree rings that indicate much more powerful outbursts, as high as X285.

Modern scientists have attempted to use modern techniques to better understand the Carrington Event. In 1859, Carrington along with other astronomers had recorded detailed sketches of the active region, or cluster of sunspots that produced the white light flare. There are also auroral reports from Eurasia and Oceania. Finally, scientists have attempted to contextualise the Carrington Event by comparing them to other solar storms. Ice core data from Antarctica indicates a total of 70 strong nitrate peaks between 1561 and 1950, with the strongest peak for the Carrington Event. However, the link between these nitrate spikes and solar outbursts are tenuous.

Considering its unexpected disturbances it introduced to incipient technology, the Carrington Event is considered as a benchmark for extreme weather events, in terms of its sudden ionospheric disturbance, solar wind velocities, the energies of the solar wind particles, magnetic disturbances, and the spectacular displays of polar lights. The modern scientific consensus is that the Carrington Event was extreme, but not unique, with similar events in 1872, 1909, 1921, 1989 and 2003. The Carrington Event took place during Solar Cycle 10, which have been continuously monitored since 1755. The Carrington Event likely took place during the peak of Solar Cycle 10.

The Carrington Event is synonymous with the most extreme geomagnetic storm conditions and is used as the worst case scenario for fortifying modern technologies against Geomagnetically Induced Currents (GICs). However, there are even more powerful solar storms, solar superstorms that are known as Miyake Events. These superstorms can be more than 100 times as powerful as the Carrington Event. The signs of these superstorms are found only in ice cores and tree rings, and have never been witnessed by modern humans. Over the past 15,000 years, there are six of these solar superstorms known. While modern technologies can survive solar storms as powerful as a Carrington Event, it may take up to a decade to recover from a Miyake Event.