By signing in or creating an account, you agree with Associated Broadcasting Company's Terms & Conditions and Privacy Policy.

By signing in or creating an account, you agree with Associated Broadcasting Company's Terms & Conditions and Privacy Policy.

New Delhi: The debate over India's nuclear energy has never been settled. for decades it has moved between two competing pressures- on one side lies the pressure of energy security and climate commitments, and on the other concerns around safety, accountability and public trust. The Government's new Atomic Energy Bill 2025, known as the SHANTI Bill (Sustainable Harnessing of Advancement of Nuclear Energy for Transforming India), attempts to navigate this uneasy terrain.

The Bill opens the door for private players in India's nuclear power sector, which is a revolutionary shift for an industry that has remained firmly under state control. But, at the same time, the bill introduces provisions that have raised concerns about accountability and compensation in the event of a nuclear accident.

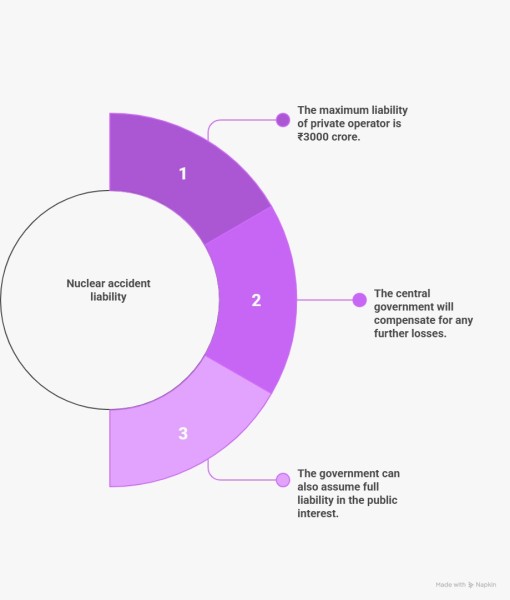

The SHANTI Bill's liability cap is the most debated clause. Under this, a private operator’s maximum liability in the case of a nuclear accident is limited to ₹3,000 crore. The government would bear any damage beyond that threshold. This raises a critical question: would this sum be sufficient to compensate victims and address long-term environmental harm in the event of a significant nuclear accident?

Nuclear power currently contributes about 3 percent of India’s total electricity generation capacity. but the government wants it to grow sharply. The government has set an ambitious target of achieving 100 gigawatts of nuclear capacity by 2047, including power generation through indigenous Small Modular Reactors (SMRs).

This target will require large and sustained capital investment. Public funding alone is unlikely to be sufficient. The SHANTI Bill is designed to address this gap by allowing licenses to be issued to public sector entities, joint ventures, and domestic private companies for building and operating nuclear power plants.

According to the government, private participation could speed up construction timelines, ease financing constraints, and help India meet its climate commitments without relying heavily on fossil fuels.

It is important to note that the bill does not hand over the entire nuclear ecosystem to private players. The most sensitive part of the sector- the nuclear fuel cycle- remains under strict central government control. Exploration, mining, ownership, and management of uranium and thorium will continue to be handled exclusively by the state.

Officials argue that this control is non-negotiable. Nuclear fuel is dual-use, with implications beyond civilian power generation. It can be used for electricity generation as well as strategic and defence purposes. Retaining monopoly over these resources, is essential to prevent security risks and maintain strategic oversight.

However, alongside this strategic safeguard lies the most controversial provision. The Bill limits the maximum liability of a private operator in the event of a nuclear accident to ₹3,000 crore. Any damage beyond this amount would be borne by the government.

By capping a private operator’s liability at ₹3,000 crore, the Bill makes financial exposure predictable. Companies know in advance the extent of their legal exposure. Insurance becomes easier to structure. Financial risk stays capped.

But this is precisely where public concern begins. In the case of a large-scale nuclear accident, would a liability cap of ₹3,000 crore be adequate to compensate victims and restore environmental damage? Global experience suggests otherwise.

India does not need to look far for an example of how weak accountability frameworks can leave victims without justice. The Bhopal Gas Tragedy of 1984 remains one of the world’s worst industrial disasters. A leak of methyl isocyanate gas killed around 3,800 people immediately. Later estimates put the death toll at nearly 24,000.

Despite the scale of the tragedy, legal consequences were limited. In 1989, MNC Union Carbide reached a settlement of about $470 million with the Indian government, an amount widely seen as inadequate given the long-term human suffering and environmental damage.

The company’s chairman, Warren Anderson, was arrested during a visit to India but released on a bond of ₹25,000. He later fled the country and never returned. Declared a fugitive, Anderson faced no meaningful accountability. India’s extradition efforts also failed, exposing the weakness of legal frameworks in dealing with large industrial disasters.

Japan’s Fukushima nuclear disaster in 2011 offers a contrasting model. Triggered by a massive earthquake and tsunami, the nuclear accident forced large-scale evacuations. According to Japan’s Fire and Disaster Management Agency, 71,124 people were displaced by February 11.

The plant was operated by TEPCO, a private company. Under Japanese law, nuclear operator liability is unlimited. According to OECD-NEA, TEPCO was required to maintain insurance coverage of ¥120 billion (US$1.1 billion), with additional government-backed mechanisms stepping in when costs escalated.

The Japanese government later created a special compensation fund supported by government loans and industry contributions, raising nearly ¥5 trillion (US$50 billion). According to World Nuclear Association data, by 2021, compensation payments to Fukushima evacuees had reached ¥9.7 trillion (around US$70 billion), funded through a mix of TEPCO payments and public resources.

In the United States, the Price–Anderson Act provides a compensation pool of about $13.6 billion, offering another example of how nuclear risk is collectively insured.

These cases underline a simple reality: the financial impact of major nuclear accidents is often far greater than initial estimates. The SHANTI Bill aims to accelerate nuclear expansion, reduce legal uncertainty, and attract private capital, while keeping strategic control in government hands.

What it does not resolve is the core concern at the heart of the debate, whether limiting a private operator’s liability to ₹3000 crore places a fair share of risk on companies, involved in an industry where failures can impose enormous social and environmental costs.

As India moves ahead with its nuclear ambitions, that question is likely to remain central and contentious.