By signing in or creating an account, you agree with Associated Broadcasting Company's Terms & Conditions and Privacy Policy.

By signing in or creating an account, you agree with Associated Broadcasting Company's Terms & Conditions and Privacy Policy.

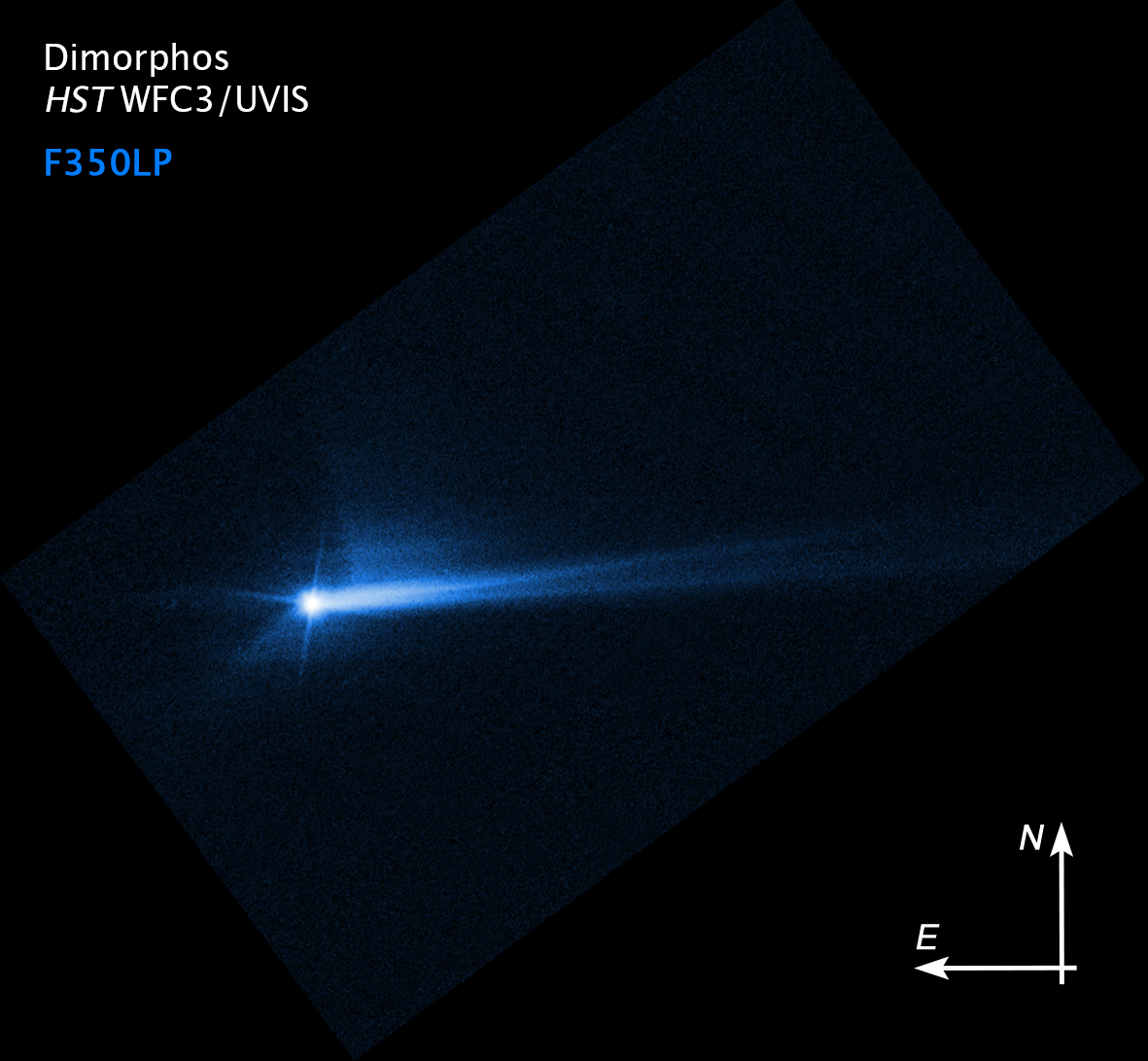

On 26 September, 2022, NASA’s Double Asteroid Redirection Test (DART) mission slammed into the asteroid Dimorphos, a 160 metre wide moonlet in orbit around a larger asteroid Dimorphos, 780 metres in diameter. For the first time, humans had demonstrated the capabilities of deflecting an asteroid. The mission was an incredible success, with the orbit of the moonlet reduced by 32 minutes. A kinetic impactor is a simple, straightforward, elegant yet violent approach to deflecting an asteroid, by ramming a spacecraft into it.

Hubble image confirming the impact. (Image Credit: NASA/ESA/STScI/Hubble).

The sooner a potential impactor is identified, the lesser energy is required to push it to a safer orbit. The asteroids that threaten the Earth are larger than 140 metres across, and are considered City-Killer asteroids. Asteroids of similar size strike the planet about once every 20,000 to 30,000 years. It takes a lead time of between five to ten years to mount a mission such as DART with the present technological capabilities of humans. Despite having proven the capability, evacuations remain the only real response to a potential impactor.

The DART impact test taught humans several crucial lessons. The first of these is that kinetic impactors work spectacularly. The deflection was 25 times in excess of the minimum calculated threshold. The shift might not seem much, but when applied years in advance, it could steer an asteroid clear of the Earth. The composition of the asteroid matters, a solid chunk of rock or metal might absorb more of the impact. However, rubble pile asteroids are easy to deflect, the ejected loose material acting as thrust from rockets, amplifying the push of the impact.

Dimorphos as seen by DART just before the impact. (Image Credit: NASA).

The test also revealed gaps in the capabilities of humans. It is far more difficult to move asteroids with a homogenous bulk compared to a clump of boulders loosely held together by the tenuous grip of low gravity. A kilometre wide asteroid is much tougher to deflect, and even harder to monitor. While the DART mission was successful, it produced a swarm of boulders, some larger than six metres across. These ejected fragments would pose their own impact risk if a kinetic impactor, or for that matter, nuclear explosives are used to deflect larger, more homogenous asteroids.

Dimorphos was only 160 metres wide, for asteroids 140 metres wider and above, tens or even hundreds of impactors would be necessary for a successful deflection. A denser, larger asteroid might require multiple impactors to maximise the momentum transfer. Simulations indicate that one impactor is required per 100 metres of diameter, a figure that doubles for denser targets. A City Killer asteroid on an impact trajectory to the Earth may require a dozen or more kinetic impactors for a successful deflection.

The mission and the gaps in capabilities that it revealed has highlighted the need for spotting asteroids, determining their trajectories, and tracking the swarms of rocks around the Sun continuously over years. If we could identify a potential impactor decades in advance, then deflecting them would require significantly less energy and resources. Our technologies, and indeed our mathematics itself are not good enough to predict the precise orbits of asteroids so far into the future. Our astronomical instruments are not sensitive enough to determine the compositions of asteroids. These are the areas that humans have to work on to improve our planetary defence capabilities.

While the DART mission was an incredible success at altering the orbit of the target asteroids, scientists and engineers are exploring a range of viable options to deflect asteroids, especially in scenarios where kinetic impactors might not work, such as large asteroids or short warning times. These methods leverage diverse principles of physics, including gravitational forces and nuclear energy, to provide flexible, scalable solutions for planetary defence that can be combined into a potent cocktail. These approaches include laser ablators, ion-beam shepherds and nuclear explosives.

Illustration of a gravitational tractor. (Image Credit: Dan Durda (FIAAA, B612 Foundation)

One particularly efficient method may be gravity tractors, which involves parking a spacecraft near an asteroid, using its bulk mass to gravitational tug the asteroid off its collision course. This method is particularly effective over decades. The spacecraft will not even touch the asteroid, but its mass would exert a continuous force. The elegance of the approach is the precision, and the asteroid is not destroyed or altered in any manner, which makes it an ideal way to deflect an asteroid without the risk of fragmentation. The approach is not considered practical as it requires significant lead times, and is more effective on smaller asteroids.