By signing in or creating an account, you agree with Associated Broadcasting Company's Terms & Conditions and Privacy Policy.

By signing in or creating an account, you agree with Associated Broadcasting Company's Terms & Conditions and Privacy Policy.

Europa is a moon of Jupiter that may be one of the best places in the solar system to find alien life. The outermost layer of the moon is a shell of ice up to 50 kilometres in thickness. Scientists suspect that Europa hosts a global subsurface saltwater ocean beneath the cracked, gleaming ice shell. Given a source of energy and the right conditions, this subsurface ocean may be teeming with life. The gravitational interaction with Jupiter squeezes and stretches the Moon, providing the energy necessary to keep the interior warm. This Ocean World may host a rich aquatic biosphere.

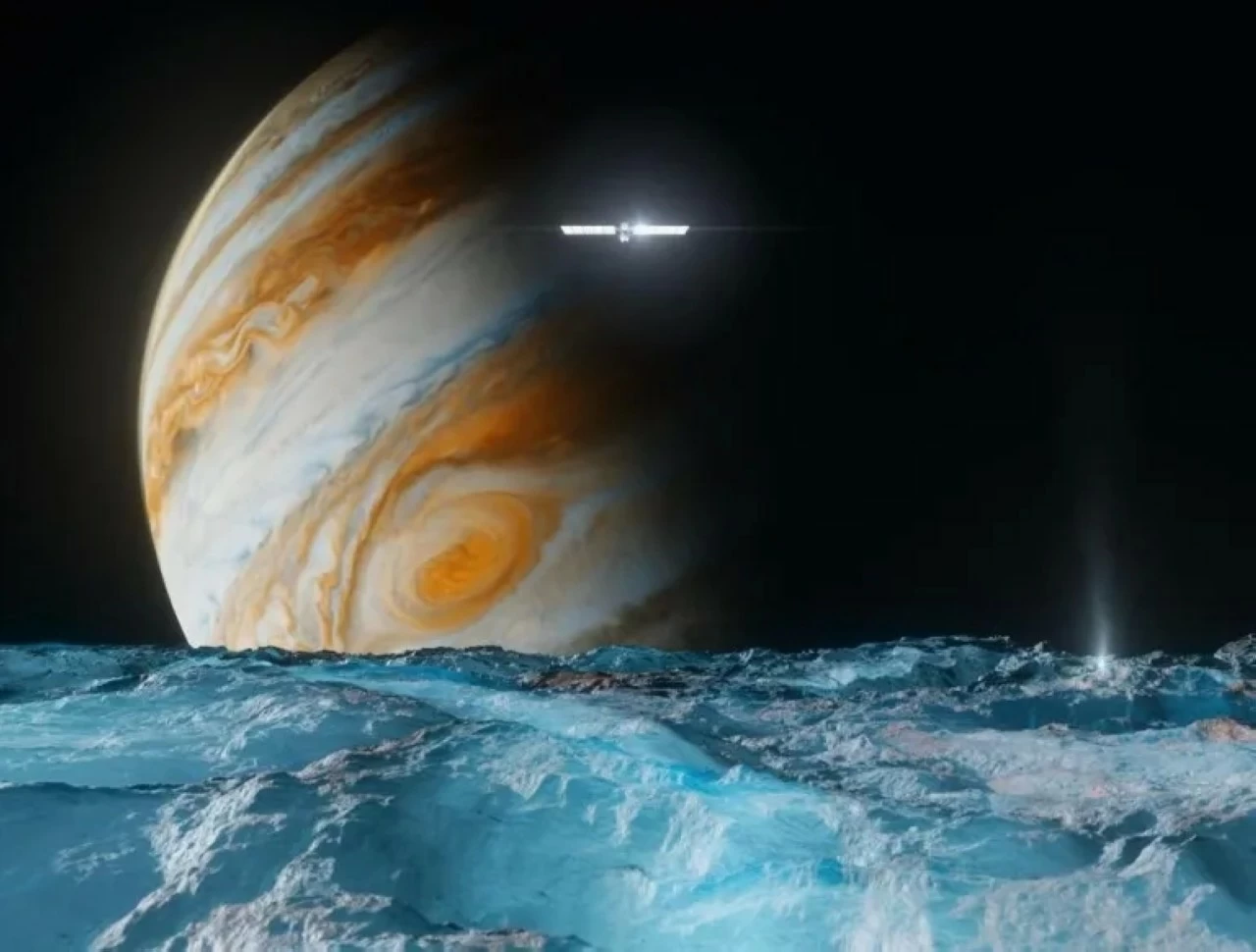

Europa as seen by Juno. (Image Credit: NASA).

Europa is about 90 per cent the size of the Moon, measuring 3,100 kilometres across. The surface is a shell of bright ice, that makes it very reflective. Reddish streaks known as linear crisscross the ice shell. These fractures indicate the constant stress from the tidal forces, because of the immense gravity of Jupiter. The surface is young, impact craters are rare, indicating active processes that reshape the world. Most of the ice crust is less than 60 million years old. There is a tenuous atmosphere above the ice, composed mostly of oxygen. This atmosphere is produced by the action of sunlight, that breaks down the water molecules on the surface.

Multiple independent lines of evidence indicate the presence of a subsurface ocean beneath the kilometres thick ice shell. The magnetic field of Jupiter is distorted around Europa. The patterns in the distortion match expectations of what would happen if a slaty, electrically conductive ocean existed beneath the crust. The cracked, deformed ice on the surface resembles the polar ice sheets on Earth, floating on liquid water. The Hubble Space Telescope has discovered occasional plumes of water vapour or geysers erupting from the surface of Europa. In these spouts, water from the deep interior of the moon reaches space. Models indicate that the ocean could be between 60 and 150 kilometres deep, containing about twice the volume of all the oceans on Earth.

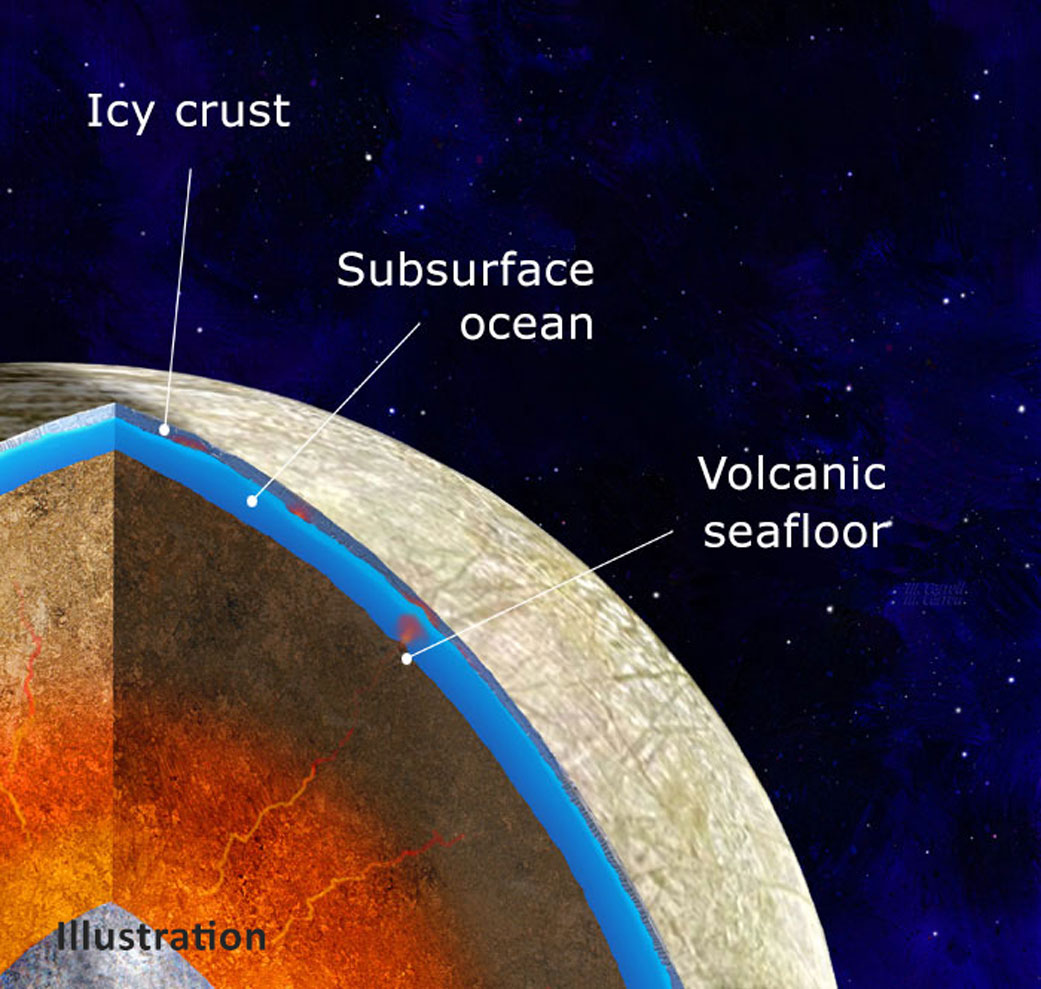

Scientists do not know exactly how thick the ice shell on Europa is. Estimates vary between 15 and 50 kilometres. If the shell is thin and dynamic, it can allow for the exchange of chemicals between the surface and the ocean, transporting nutrients into the interior, and aiding any potential life forms. A thick and stagnant ice shell would isolate the ocean, reducing the amount of energy and materials from the surface available to the inhabitants. Some regions on Europa have a chaotic terrain, with fragmented and rotated ice blocks, indicating active geology. These features are possibly caused by localised melting, or the upwelling of warmer ice or water from the interior. There may be geothermal vents on the floor of the subsurface ocean.

NASA’s Galileo spacecraft orbited Jupiter between 1995 and 2003, flying past Europa 11 times, capturing crucial data on its surface features and magnetic field. More than two decades after the end of the mission, scientists reexamined the data and discovered that the spacecraft could have flown right through one of the plumes erupting from Europa. The Hubble Space Telescope has directly imaged features that appear to be plumes. These spouts of water provide a way for spacecraft to investigate the composition of the subsurface ocean, and potentially determine its habitability.

Interior of Europa. (Image Credit: NASA).

On 14 April, 2023, the European Space Agency launched the Jupiter Icy Moons explorer that will investigate all the moons in orbit around Jupiter suspected to host global subsurface oceans: Europa, Ganymede and Callisto. On 14 October, 2004, NASA launched the Europa Clipper mission, a spacecraft dedicated to assessing the habitability of the ice moon. The spacecraft is expected to reach Jupiter in 2030, and will perform dozens of close flybys, mapping the surface of Europa in detail, conclusively determining the thickness of the ice, investigating the plumes of water, and studying the magnetic environment to characterise the subsurface ocean.

Europa poses an exciting challenge for space exploration, with scientists developing advanced concepts that can potentially be used in follow-up missions. These includde landers equipped with mass spectrometers to analyse the chemistry of the surface, ice-penetrating probes that can drill through the shell, or robots that heat their surfaces to melt the surrounding ice and sink to the ocean. A flexible, snake-like rover can potentially reach the subsurface ocean through cracks in the crust, and a drilling rover can unleash a swarm of smartphone-sized aquatic drones to explore the interior of Europa. These submarine drones may encounter something else already swimming in the oceans of Europa. While Europa is one of the most promising targets in the search for extraterrestrial life, it is also one of the most challenging.