By signing in or creating an account, you agree with Associated Broadcasting Company's Terms & Conditions and Privacy Policy.

By signing in or creating an account, you agree with Associated Broadcasting Company's Terms & Conditions and Privacy Policy.

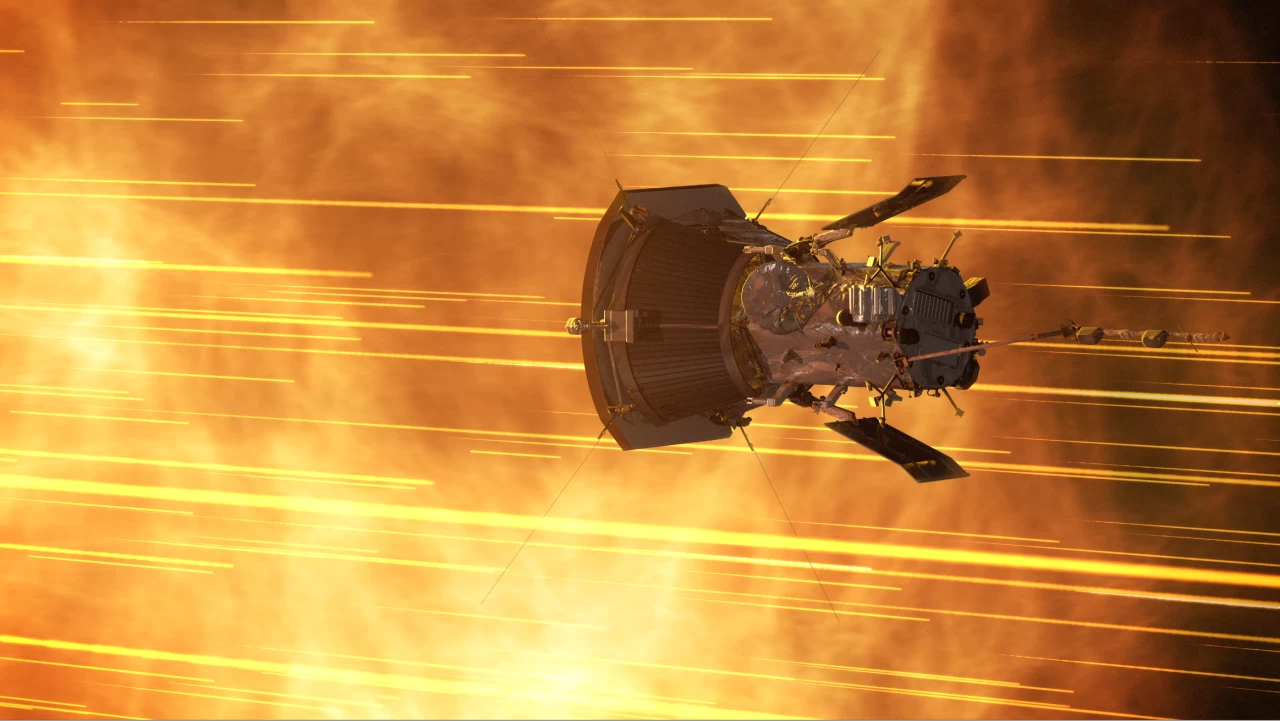

The Sun is essentially a dense ball of hot gas or plasma, with a nuclear reactor at the cure where hydrogen is fused into helium. In eruptive events, the Sun hurls clouds of charged plasma outwards into space, that influences the entire Solar System, causing outgassing on the Moon, inducing geomagnetic storms at the Earth and stripping away the atmosphere on Mars. During its close approach to the Sun in December 2024, the Parker Solar Probe tracked some of this material returning to the Sun.

The ejected material returning to the Sun changes the solar atmosphere in subtle but significant ways, setting the stage for the course of the subsequent coronal mass ejection. The phenomenon is called 'inflows' and has previously been detected by the Solar and Heliospheric Observatory (SOHO), a joint mission between NASA and ESA, as well as NASA's Solar Terrestrial Relations Observatory (STEREO) spacecraft, but the proximity to to the Sun allowed the Parker Solar Probe to observe the process in unprecedented detail.

The inflows allows scientists to track how the Sun recycles some of the ejected material. Scientists were able to determine the speeds and sizes of the blobs that returned to the surface of the Sun or the photosphere. These returning blobs influence the swirling magnetic fields beneath, reconfiguring the solar magnetic landscape, that can potentially alter the trajectories of the subsequent coronal mass ejections. This reconfiguration can be sufficient to make a difference on whether a coronal mass ejection washes over a planet or not. Researchers are using the observations to refine models of space weather and the complex magnetic environment of the Sun.